An hour ago, I rushed into the kitchen to inaugurate a gift—the pineapple vendor’s knife. It emerged unwillingly from its newspaper scabbard, still sticky from its last victim. But scrubbed clean, the slender blade glinted with impatience.

I hesitated.

What, after all, was a pineapple? A brute chunk, managed with a machete. This knife demanded more.

A tomato bulged trustingly on the chopping-board.

Invisible Japanese chefs jostled for a ringside view as I prepared to transform the tomato’s squish into elegant wafers, one cell thick.

Five glassy panes of scarlet slid off the steel, each balancing a wobbly pinhead of jelly.

The chefs exhaled in Japanese.

Also Read | Footloose in Ferghana

Faster now, ten, twelve—

Ouch!

That last slice was definitely not tomato.

The chefs left, sniggering.

The burning crater on my index finger bubbled up and overflowed. Dismay overtook pain.

Bandaid in place, I told myself I still had nine functioning fingertips, losing one temporarily wasn’t the end of the world.

Oh, but it is.

Lose a fingertip, and you’ve lost the world.

The fingertip made us human.

What? Did I hear you say brain?

Nah, it is the fingertip that made the brain.

A quivering mass of nerves

We began making tools more than 3 million years ago, when the brain was a puny pecan. We had recently been gifted 10 sensors that connected us with marvels we hadn’t noticed for a million years. Swamped with information screaming to be understood, naturally, we grew a better brain.

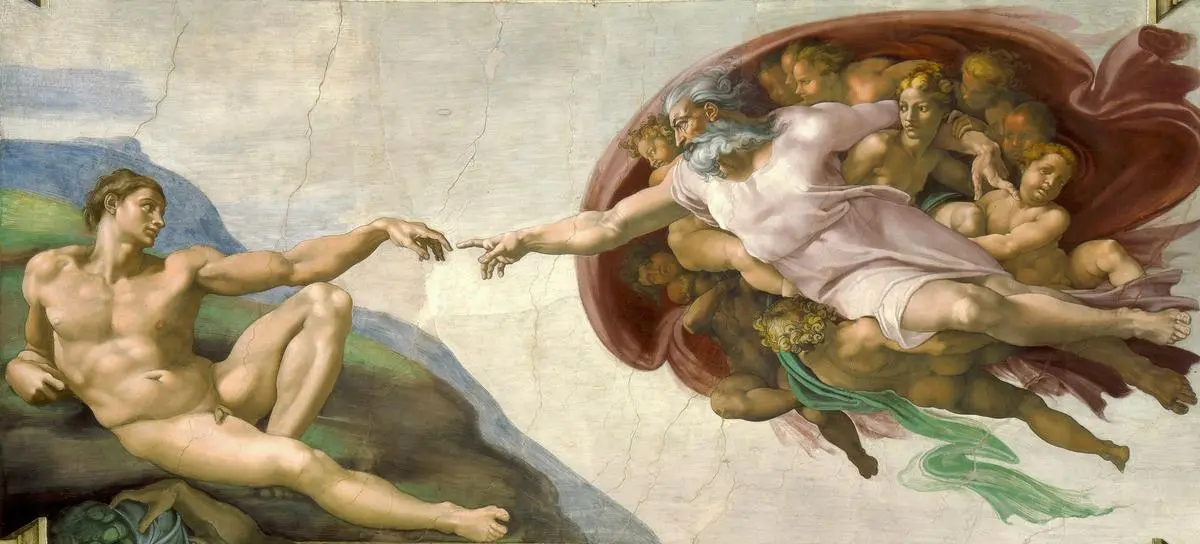

Detail from Michelangelo’s fresco, “The Creation of Adam”, where God animates the first man with a touch of his fingertip.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

And now, when we’ve pretty much lost the fingertip, what does that spell for the brain?

I peeled off the Band-Aid for a closer look at my injured fingertip.

What did I lose with that sliver of skin?

The fingertip lacks the seductive politesse of hair. It is as naked as naked gets. Dermatologists, that rude tribe, call fingertip skin glabrous, but that is a low jibe. Its very baldness makes the fingertip sentient. The cushiony end is a quivering mass of nerves, crowded yet disciplined, to detect the world factually—temperature, heft, texture, dimension, shape—to establish the undeniable reality of experience.

Minus this probity, the world would be a hallucination. Seen and heard, but without the factual evidence of touch. Call it Maya. Or cyberspace.

The throbbing crater on my fingertip cannot register factual evidence, because that missing bit of skin carried all the sensors: three sorts of specialised receptors, about 50 of them to the millimetre. They chatter to nerves about touch, indentation, pressure—fleeting or continuous—and the brain translates this into information the rest of my body can use. Also, without that cap of skin, I can feel neither pleasure nor pain. I am benumbed, clueless, adrift.

The fingertip welcomes the world

The fingertip, demeaningly called “pulp”, is the most truthful part of the body. Lacking the euphemism of hair, it cannot alter facts by even a solitary vibrissa. Missing the thickness of the sole, no padding protects it. It isn’t the most sensitive—our genitals are far twitchier—but it is more open-minded. The competition is specialised for just one thing. The fingertip welcomes the world.

The pulp, a bit of which my crater revealed, doesn’t look very different from the tomato still aquiver on the chopping-board. It is a gelatinous blob of fat, squelchy with blood contained in a fine mesh of capillaries looped with nerves. And all that is firmly bolted down onto a tiny bone.

Crude, eh? It is the pulp that grips my pen, and when words have spilled, it is the pulp that measures the pinch of salt that goes with them. Constant friction can thicken the skin and deaden sensation, and clue Mr Holmes on your profession. My hands would have puzzled him. The writer’s bump I wore with pride for 40 years has all but disappeared after 25 at the computer. I panic occasionally over that. Perpetual slavery to the keyboard denies my fingertip its natural function—to connect the body to the outside world.

The Anthropocene, our present geological age, is all about that disconnect. As evolution’s top dog, Homo sapiens has been possessive, exploitative, destructive. Did it have to be a war between us and the elements? Between us and other species? Between our selves? What has it ever wrought but death and disease? And whatever happened to sapience?

Going deeper

Hubris doesn’t stop there. This disconnect goes deeper.

Also Read | Mandu’s gigantic tamarind: Nuggets of hope

We don’t exist in our bodies anymore. Like in an ancient fairy tale, identity has migrated into the image, the metabody, trapped not in the mirror, but in the lighted screen. When proof of life is needed, shoot a selfie! And the fingertip, tap tap tapping its way to dusty anaesthesia, won’t argue. With nothing to engage its skills, the fingertip is more than ready to be pensioned off. Besides, it is changing. The clever whorls and ridges designed for a prestidigitator’s sureness are now standard spyware.

For how long?

They will be erased, glazed over, as the fingertip grows alarmingly smooth. The top clear layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, is kept sentient by a 14-day cycle of shedding and renewal. That will not last when keratin grows thicker and dead cells overstay. The fingertip will soon wear a protective thimble and effectively end its 3 million year career as a peripheral brain. At the first touch of love, the pulp will no longer dimple, no thrill will tingle up and down the spine. Objects will slip and fall and shatter. You will singe your mouth on a hot potato because you did not drop it. And the brain, self-absorbed and solipsistic in its isolated trance, will forget the art of reason.

Life is too brief for that. Our species, now Homo stultus, is out of touch with the reality that defines us. The body is our only claim to sapience, it is the only home we have. So till death evicts us, why not rejoice in it?

Hello, fingertip!

Kalpana Swaminathan and Ishrat Syed are surgeons who write together as Kalpish Ratna. Their book Bahadur was published in 2023.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/the-human-fingertip-evolution-sapience-and-digital-disconnect/article69690343.ece