The novel’s female characters strike one as refreshingly contemporary and independent.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStock

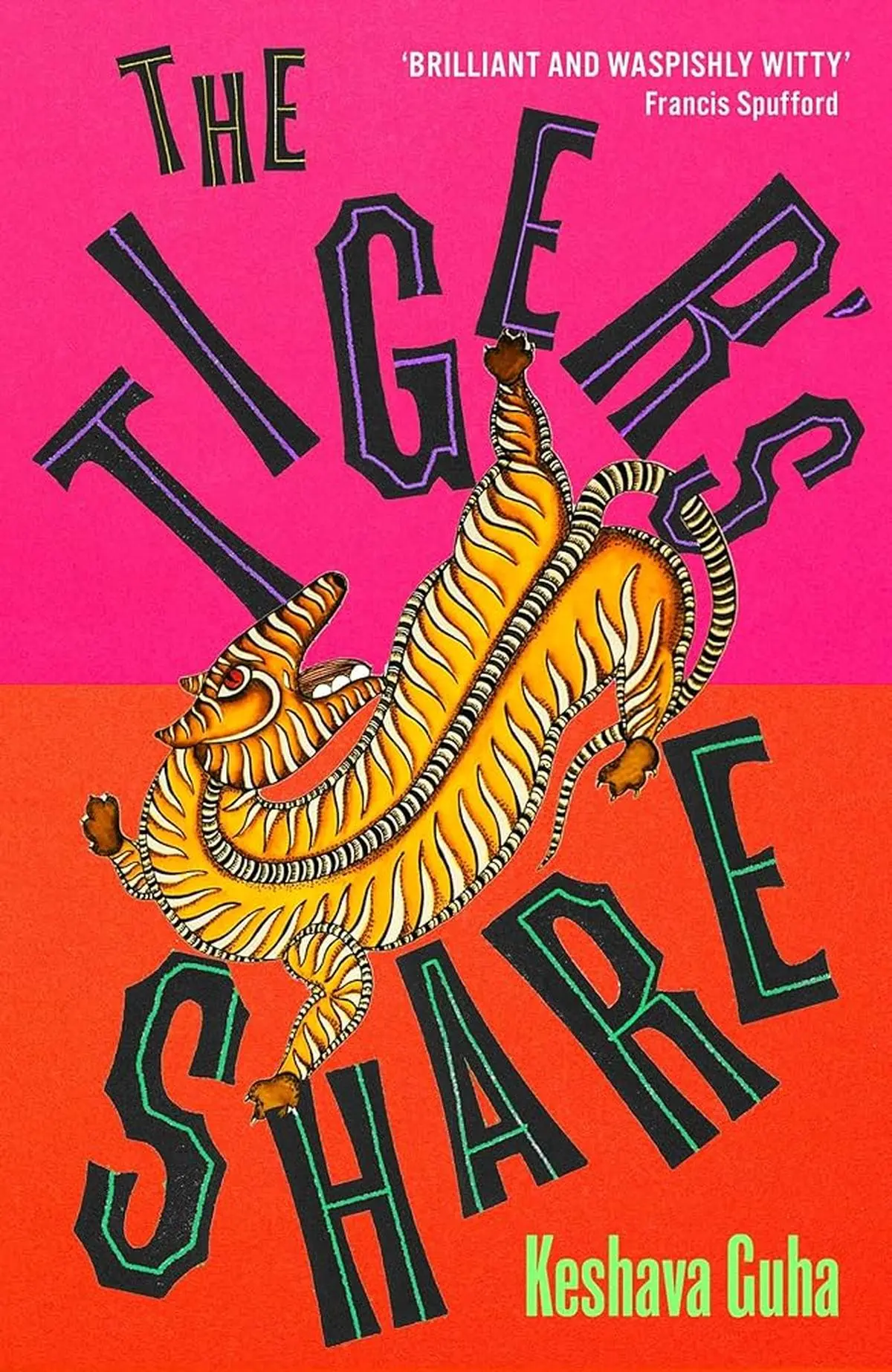

It is difficult to resist a novel that Amitav Ghosh, in one of the three heavyweight endorsements paratexting it, attributes to “an astute and insightful observer of contemporary India”. This comment mostly holds true, although I would have preferred to say “Delhi” instead of “India”. Keshava Guha’s The Tiger’s Share is a consciously “Delhi” novel, and for me that is a point in its favour.

Another thing in its favour is the novel’s engagement with family property. Now, at least in north India, the two topics that come up most often in conversation are property and the state of one’s stomach. Despite Indian English fiction being full of foodie segments, it seems to leave out any extensive narrative on “gas” and related matters that north Indians discuss frequently on trains and buses. More surprisingly, family property—as a perennial matter of contestation and litigation—is also mostly missing from Indian fiction in English, though there is hardly any middle- or upper-class family in north India that does not have a torturous story to tell about it.

The Tiger’s Share

By Keshava Guha

Hachette India

Pages: 256

Price: Rs.699

The Tiger’s Share is about two families where property does raise its divisive hydra-head, at least initially. Tara, the narrator, is a successful Delhi lawyer and has little sympathy for her younger brother, who has been doing the kind of floating writerly and cultural degrees abroad that seem to have become permissible in upper-middle-class families now. When their father, Baba, who has made a small fortune for himself as a meticulous CA, decides to retire and implies that his five houses might not go to the two children, Tara is not overly concerned. But her brother—who has, as they used to say, expectations—is bothered, and both the brother and the mother suspect Tara of legal subterfuge in the matter.

Also Read | Eyewitness to a withering republic

Around the same time, Lila, a potential friend who gradually turns into a real friend, approaches Tara with her own problem. Lila’s father, a refugee from Pakistan who had become extremely rich as an astute businessman, has just passed away. Lila has a brother, Kunal, adopted, who now wants to take over the father’s mantle, which means having the women in the family look up to him as the (alpha) head. This Lila refuses to do, leading to property-related tensions.

The Tiger’s Share is about two Delhi-based families.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Unfortunately, though, this rich promise of a real property-litigation novel, narrated from a gendered perspective, is not fully redeemed. It does not disappear but recedes into the background, with Tara and Lila opting for different solutions. Then Baba’s mysterious retirement decision takes centre stage towards the end of the novel. It is an intriguing decision, though it further defuses the property aspect, which seems to be in keeping with the narrator’s—and perhaps the author’s—position. The conclusion should not be revealed, but I have to say that while it is interesting from an existential perspective, it is also comfortable from a propertied and political one.

Nell Freudenberger, in her rave blurb, notes the “shocking conclusion” of the novel, and probably the conclusion is shocking to Western readers. But without revealing the conclusion, one needs to add that Indians who are familiar with the Boddhisattva story about the tiger with two malnourished cubs, and who are aware of, say, Parsi funeral customs, might be able to anticipate the conclusion by the fourth quarter of the novel.

Immaculate narration

This is a gripping novel, narrated immaculately and at a fast clip. It contains female characters who strike one as refreshingly contemporary and independent, which is a relief, but too often talk in an identical fashion, which is not. The most interesting characters of the novel are the two men (alas) who do not fully “belong” to its elite classes: Baba, who has struggled his way up and managed to do so with exceptional success, and Kunal, whose adoption has not eased his own struggle to shape himself in the new India of old “traditions”. Baba is narrated with awed love by Tara, and Kunal with a degree of class-educational dislike—both these aspects leave many questions unasked, adding to the under-narrated fascination of these two characters.

Also Read | Wings of desire

There is a kind of brisk confidence in the narration, which fits the narrator but can also sometimes turn irritating. I am not sure if this is intentional. If it is, then it remains underdeveloped in a novel that is usually gripping, always readable, and quite often humorously perceptive about the Delhi cocktail circles being surveyed. Not to mention the smaller characters in those circles, such as Wojciech Zielinski, the desperately popular, uber-fit cultural attaché, or Vicky, the perfectly groomed cultured millionaire heir with an entitled attitude to sexual exploitation.

Tabish Khair is an Indian novelist and academic who teaches in Denmark.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/the-tigers-share-review-keshava-guha-delhi-literary-fiction/article69682203.ece