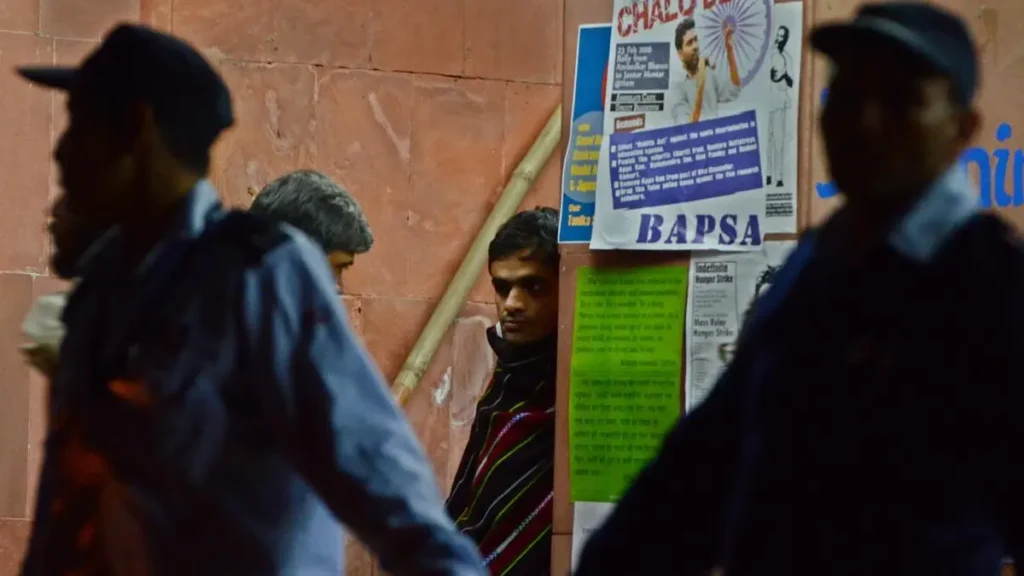

Umar Khalid in December 2016. Drawing on literature, science, and philosophy, his letter from prison becomes a meditation on time, memory, and the ideological repression of Muslims and dissenters.

| Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma/The Hindu

The latest letter sent by Umar Khalid, a former Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) history scholar who will in September complete five years in Delhi’s Tihar jail in a bogus case based on one-sided charges supported by flimsy evidence, makes for a good reading, not least because he refers to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead, a novel that the writer based on his four years in a Siberian prison camp where his hands and feet were always shackled. Dostoevsky was considered one of the most dangerous convicts. Today, he is considered among the greatest writers. Some believe that The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment will give you a better glimpse of life’s meaning than anything else.

Umar quotes from the novel: “We are not alive though we are living, and we are not in our graves though we are dead.” Umar notes that though 150 years have passed since the novel and the world has changed unrecognisably, “… at many places, I felt as if he was narrating things and occurrences that I see around myself here at Tihar.”

Like many prison diaries from around the world over the years, the thing that Umar ruminates over all else is the nature of “time”. Novelists have forever experimented with the nature of time and memory, most famously in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu; Albert Einstein said that time was another dimension that was distorted, along with space, by gravitationally dense objects; scientists keep pushing sub-atomic particles backwards in time in pursuit of the grand unified theory that will explain all physical phenomenon; philosophers argue whether time informs us or we construct time with the purpose of ordering events; and musicians, well, like Miles Davis’s album Kind of Blue, they float in and out of time.

Umar says he has lost his optimism, and one can’t blame him; the way the government stubbornly refuses to grant him bail makes it clear that he is to be kept in jail so long as Prime Minister Narendra Modi is in power; he is an example to be made to all dissenters and to all Muslims—that the State will pick you up and throw you away if you try and exercise your fundamental right of speech and so much as cheep.

Also Read | Umar Khalid granted interim bail in 2020 Delhi riots case

Umar has had a long history of speaking truth to power, be it asking questions about the disappearance in 2016 of JNU student Najeeb Ahmed; his allegedly provocative speeches at a Elgar Parishad rally following which there was caste violence in 2018; and the peaceful protest at Shaheen Bagh in 2019-2020 against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which Muslim women worried would be used against their community. (It forewarned of Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s recent actions of pushing Muslims into Bangladesh, whether they are Bengalis or not, and aping US President Donald Trump in going after non-majoritarian residents.)

Free men vs. real men

Umar defines the difference between a free man and a jailed one as one’s view of “real life”. He says that a free man is caught up in the world of life, but for a prisoner: “There is life for him too—granted prison life—but whatever the convict may be and whatever may be the term of his sentence, he is instinctively unable to accept his lot as something positive, final, as part of real life. Every convict feels that he is, so to speak, not at home but on a visit.”

Hence, this state of impermanence makes managing time difficult. Umar copes by seeing time not as a chunk, but by breaking it into periods between court dates.

Protesters during a demonstration against the CAA on December 19, 2019, in New Delhi. Khalid’s letter from Tihar jail traces how the CAA marked a turning point in India’s democracy, where peaceful dissent met with punitive state power.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

He mentions a prisoner who has been here for 29 years (he came in his 20s and is now in his 50s); most life terms end somewhere after 14 years, but this prisoner is in a Trishanku-like limbo in that he was on death row but got a presidential reprieve with the caveat that he would spend the rest of his life in prison and not be eligible for bail.

Lately, the Supreme Court allowed him a furlough (short leave given for good behaviour) for 21 days. When he returned, “in the few words he spoke, he said he felt as if he was outside for 21 minutes, not 21 days”, Umar writes. It is a psychological trick of time to compress joy and elongate loneliness.

Also Read | Kapil Mishra, Umar Khalid, and the unequal weight of justice

It may seem natural that prisoners should try to use a furlough to escape and never return. Umar says that it is only new prisoners who might attempt it.

Even Dostoevsky had noted, in The House of the Dead that prisoners do not try to escape. “Dostoevsky writes that prisoners don’t run away because they value the time they have given to prison,” Umar tells us.

Time is all they have, and frankly, the State has no business in snatching it away. It is a precious resource for humans, for despite being an animal lover, I don’t see how they understand or value time in the way that we humans do. Yes, some animals have a great memory, like elephants or Argos, the faithful dog in The Odyssey, who was so overjoyed when his master returned after a decade that he collapsed dead, but this tells us nothing about their perception of time.

Finally, Umar closes with this: “Five years have passed, almost. Half a decade. That’s time enough for people to complete their PhDs and look for jobs, time enough to fall in love, marry and have a baby, time enough for one’s kids to grow beyond recognition, time enough for the world to normalise the genocide in Gaza, time enough for our parents to grow old and feeble.

“Is it time enough for our release?”

It undoubtedly is. But to say so is like banging one’s head against the abstract, ideological wall of Hindutva. It is a sign of the times where an idea is taken to be more precious than an individual life.

Aditya Sinha is a writer living in the outskirts of Delhi.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/umar-khalid-letter-prison-time-dissent-india/article69686079.ece