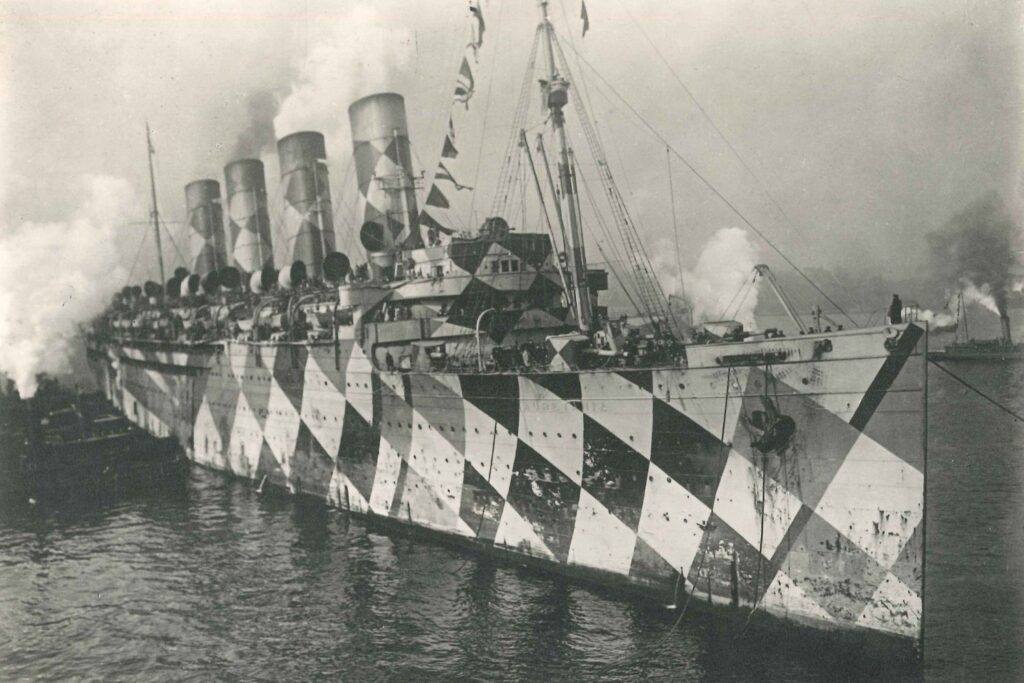

During World War I, navies painted their ships in “dazzle” camouflage, also known as “razzle dazzle.” Unlike traditional camouflage, which helps objects blend into their surroundings, dazzle camouflage used stark geometric patterns to try to confuse German U-boat captains’ perception of a ship’s direction and speed, making it harder to target. But did the dazzle actually dazzle, or did it simply look ridiculous?

Aston University researchers have investigated the efficacy of dazzle camouflage on WWI battleships by re-analyzing a 106-year-old study. According to the new paper, the unintentional “horizon effect”—when a boat seems to be traveling along the horizon, even if it’s not—was a far greater source of deception than the dazzle paint itself, exposing a key oversight in the 1919 analysis. Their findings are detailed in a study published on March 14 in Sage Journals.

In 1919, MIT naval architecture and marine engineering student Leo Blodgett conducted a study on dazzle camouflage for his thesis. The study involved painting dazzle patterns onto a model battleship and observing how the patterns affected an onlooker’s perception of the ship’s direction of travel when viewed through a periscope. Blodgett ultimately concluded that dazzle camouflage achieved its aim.

More than a century later, however, researchers Timothy Meese and Samantha Strong expressed significant concerns about Blodgett’s methods. Specifically, they suspected that the onlookers’ warped perception was not totally due to the dazzle paint.

“It’s necessary to have a control condition to draw firm conclusions, and Blodgett’s report of his own control was too vague to be useful,” Strong, a senior lecturer in optometry, said in a university statement. “We ran our own version of the experiment using photographs from his thesis and compared the results across the original dazzle camouflage versions and versions with the camouflage edited out. Our experiment worked well. Both types of ships produced the horizon effect, but the dazzle imposed an additional twist.”

The horizon effect dictates that viewers will perceive ships as traveling along the horizon even if they’re traveling at an angle of up to 25 degrees relative to the horizon. More broadly, viewers underestimate this angle, even when it’s greater than 25 degrees.

If dazzle camouflage were single-handedly responsible for the visual deception noted in Blodgett’s study, viewers should have consistently seen the front of the ship, called the bow, “twist” away from the direction of travel, according to the researchers. Meese and Strong, however, pointed out that in certain instances—specifically, when the model boat was moving away from the viewer—the onlooker saw the bow “twisting” toward them. This indicates that another factor, beyond dazzle camouflage, was influencing the illusion.

They identified the horizon effect and concluded it played a greater role in deceiving viewers than dazzle camouflage.

The researchers “knew already about the twist and horizon effects” from a previous study that Meese, a professor of vision science, co-authored in 2024. However, “the remarkable finding here is that these same two effects, in similar proportions, are clearly evident in participants [from the 1919 study] familiar with the art of camouflage deception, including a lieutenant in a European navy,” Meese explained. “This adds considerable credibility to our earlier conclusions by showing that the horizon effect—which has nothing to do with dazzle—was not overcome by those best placed to know better.”

In other words, the horizon effect hoodwinked even experienced individuals. Back then, however, “the horizon effect was not identified at all,” Meese added, so the effect was truly “deceiving the deceivers.”