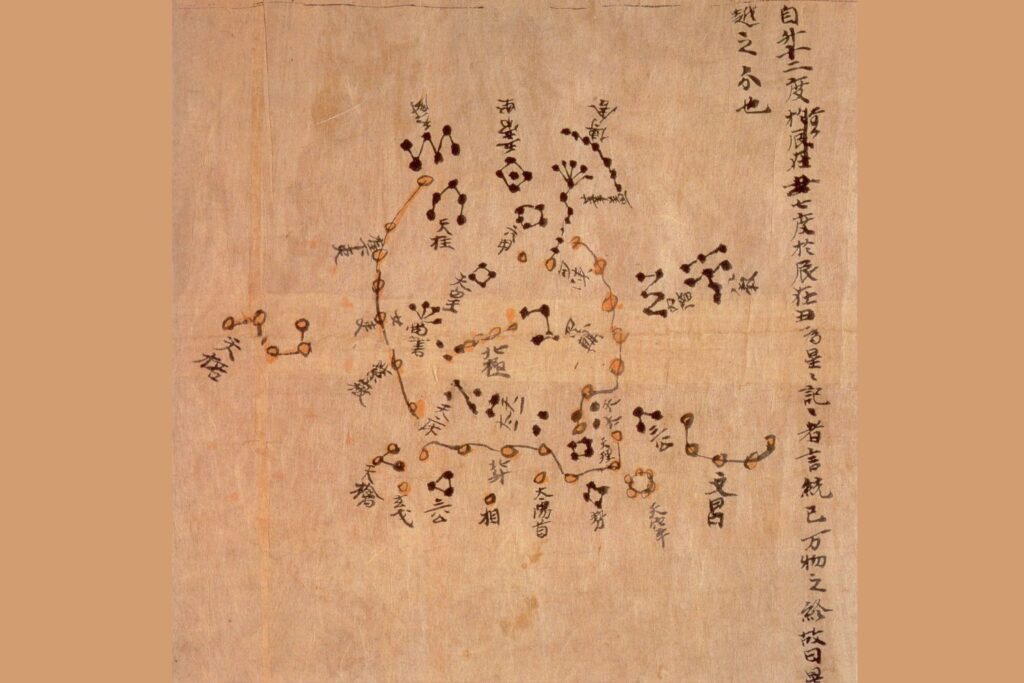

Humans have been stargazing for thousands—possibly hundreds of thousands of years. Ancient people around the globe looked to the heavens for physical and spiritual guidance. Dozens and dozens of generations later, their descendants are now arguing over which civilization created the oldest known visual star catalog in the world.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ National Astronomical Observatories claim that Shi’s Star Catalog, the oldest known star catalog in China, is actually the earliest known star catalog, period. They reached this conclusion using a technique that accounts for potential human errors made thousands of years ago. If their results prove to be true, it would mean that Shi’s Star Catalog is centuries older than the other first place contender—the one created by Greek astronomer Hipparchus. But not everyone in the scientific community is convinced.

“In comparison to the observation epochs of other ancient star catalogs worldwide, the Shi’s Star Catalog predates even the oldest Western star catalogs, affirming its status as the oldest star catalog in the world,” the researchers wrote in a study posted to the preprint server arXiv in April.

Because Earth’s axis wobbles, the location of stars in the night sky changes over the centuries in a phenomenon called precession. Researchers can use Earth’s precession to date ancient visual star catalogs by calculating the difference between historical records of the night sky and what our stars look like now.

Shi’s Star Catalog, however, has been infamously difficult to date, not least because this one catalog depicts star positions that seem to span multiple centuries. In the preprint study, the researchers outline a number of previously suggested dates: around 360 BCE; around 360 BCE with an update around 200 CE; around 440 BCE with an update around 160 CE; sometime between 100 BCE and 70 BCE; and during the seventh century CE.

“A multitude of perspectives exist regarding the observational timeframe of the Shi’s Star Catalog, with no definitive consensus reached,” the researchers admitted. As such, they decided to analyze the catalog’s 120 stars with the Generalized Hough Transform method—an algorithmic imaging technique that “statistically accommodates errors in ancient coordinates and discrepancies between ancient and modern stars, addressing limitations in prior methods,” they explained. This approach seems to confirm that Shi’s Star Catalog was first drafted around 355 BCE and then updated around 125 CE.

“In comparison, the Western tradition’s oldest known catalog, the Ptolemaic Star Catalog (2nd century CE), likely derives from the Hipparchus Star Catalog (2nd century BCE). Thus, Shi’s Star Catalog is identified as the world’s oldest known star catalog,” they added.

Some scientists, however, have a different theory: The instrument used to record Shi’s Star Catalog was off by one degree. Previous studies adjusting for this assumption date Shi’s Star Catalog around or after 103 BCE, as reported by Science. Certain historians look favorably on this later date because it aligns the catalog’s use of spherical coordinates more closely with the Chinese invention of the armillary sphere (a spherical mathematical instrument used to track the movement of celestial bodies around Earth) and their adoption of a spherical cosmological model, both of which took place in the first century BCE, according to Science.

Suggesting that people used spherical coordinates hundreds of years before the invention of the armillary sphere, as the researchers do in the recent study, would be like finding “a receipt from a gas station and somebody wants to say it’s from 1700,” Daniel Patrick Morgan, a historian at France’s Center for Research on East Asian Civilizations who was not involved with the study, told Science.

Future research may provide more answers. Whether or not the recent study proves to be true, it’s worth noting that the Western world’s Eurocentric approach has historically undervalued achievements made elsewhere, including those in ancient China. Plus, the ancient Babylonian seventh century BCE Astronomical Diaries blow both European and Asian astronomical artifacts out of the water, even though the tablets list astronomical observations via text, not visuals.