A path to pursue

Born on August 30, 1884 at Flerang in the parish of Valbo near Gavle, Sweden, Theodor (The) Svedberg was the only child of Elias Svedberg and Augusta Alstermark. The fact that his father was a works manager at different ironworks in Sweden and Norway meant that the family lived at a number of places in Scandinavia during his childhood. His father made it a point to take him out for excursions often, allowing him to develop a love for nature and a keen interest in botany.

Svedberg attended the Koping School, the Orebro High School and Gothenburg Modern School and had the privilege of being taught by some prominent teachers. These teachers were also understanding, allowing Svedberg to study on his own. This gained him access to laboratories after ordinary classes and Svedberg spent time in the afternoons at the physical and chemical labs of the school.

Stoked by the advent of new discoveries and inventions in both physics and chemistry, Svedberg went about building stuff on his own. He created a Marconi-transmitter and a Tesla-transformer this way and even arranged public demonstrations that included wireless telegraphy between two blocks of his school.

Even though he had a passionate interest in botany, he decided to study chemistry following his hands-on efforts in his school laboratories. This experience also put him in good stead when he went on to experiment with colloids later on.

A lifelong association

After matriculating from school, Svedberg began a lifelong association with Uppsala University in January 1904. It was here that he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1905, his Master’s degree in 1907 and Doctor of Philosophy in 1908.

While still studying, Svedberg accepted a post as assistant in the Chemical Institute at Uppsala. This means that Svedberg’s scientific career set off in 1905, while he was still in his early 20s. By 1907, he was given the added responsibility of serving as lecturer in chemistry in the university. It wasn’t long before a special appointment as lecturer and demonstrator of physical chemistry came through in 1909. In 1912, he was elected Professor of Physical Chemistry, Uppsala University – a position he held onto until 1949, when he was made emeritus.

It was in 1949 that Svedberg took on the role of director of the Gustaf Werner Institute for Nuclear Chemistry at the University. He remained at this post until 1967 and the institute was renamed The Svedberg Laboratory in 1986, about 15 years after his death in 1971. The facility was permanently shut down in 2016, following a decision a year earlier to implement decommissioning.

It is worth mentioning that a Nature article in 1944 speaks of a volume “compiled by colleagues, friends and pupils to celebrate the sixtieth birthday of The Svedberg.” Even though by title he was a Professor of Physical Chemistry, 31 of the 56 communications in that volume can be termed as biophysics – both a nod to Svedberg’s passion towards biological systems, and the fact that he had wide-ranging interests and activities. British physical chemist Eric Keightley Rideal, to whom the Nature article is attributed, also makes it clear that if it hadn’t been for the limitations imposed on this compilation by World War II, the “contributions would certainly have come in from all parts of the world.”

A lifetime with science

Primarily interested in colloids, Svedberg’s work mainly concerned with these particles with a size of between 1 and 100 nanometres. His 1908 doctoral thesis – Studien zur Lehre von den kolloiden Lösungen – is now considered a classic and he described a new method of producing colloidal particles. Svedberg also gave convincing evidence of the validity of the theory on Brownian movements founded by renowned theoretical physicist Albert Einstein and Polish physicist Marian Smoluchowski. In this way, Svedberg provided conclusive proof of the physical existence of molecules.

One of Svedberg’s early patents was filed on June 1, 1909. In this patent, titled “Process of Producing Colloidal Sols or Gels.” Svedberg speaks of an invention relating to the process of producing colloidal sols or gels. The patent was accepted and granted in Great Britain on May 26, 1910. It is interesting to note that Svedberg applied for this patent in four countries. What’s more, he made the applications in Denmark, Switzerland, and Austria also on June 1, 1909.

Working with a number of collaborators, Svedberg continued to study the physical properties of colloids, be it diffusion, light absorption, or sedimentation. His studies enabled him to conclude that the gas laws could be applied to disperse systems.

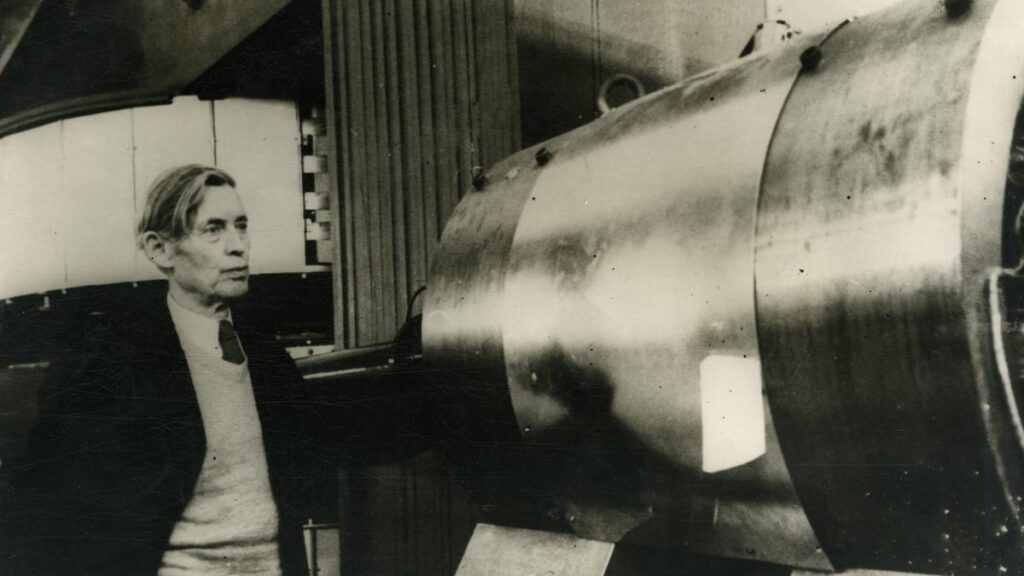

Svedberg invented the ultracentrifuge for the study of sedimentation. Using this, he could study large molecules in solution, such as proteins, carbohydrates, and high polymers. Svedberg employed centrifugal forces to better mimic the effects of gravity on particles and the first ultracentrifuge, which was constructed in 1924, could generate a centrifugal force up to 5,000 times the force of gravity.

With an ultracentrifuge, Svedberg came up with findings relating to molecular size and shape, and also used it to prove that proteins were a kind of macromolecules, paving the way for molecular biology. For his discoveries regarding disperse systems, Svedberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1926.

In his later years, Svedberg switched to nuclear chemistry and radiation biology. He made contributions to improve the cyclotron and helped his doctoral student – Swedish biochemist Arne Tiselius – as he went about researching electrophoresis to separate and analyse proteins. Tiselius himself went on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1948 “for his research on electrophoresis and adsorption analysis, especially for his discoveries concerning the complex nature of the serum proteins.”

An Indian connection

Svedberg has a couple of Indian connections – one that can be refuted, and another based on solid fact.

Did Raman and Svedberg know each other?

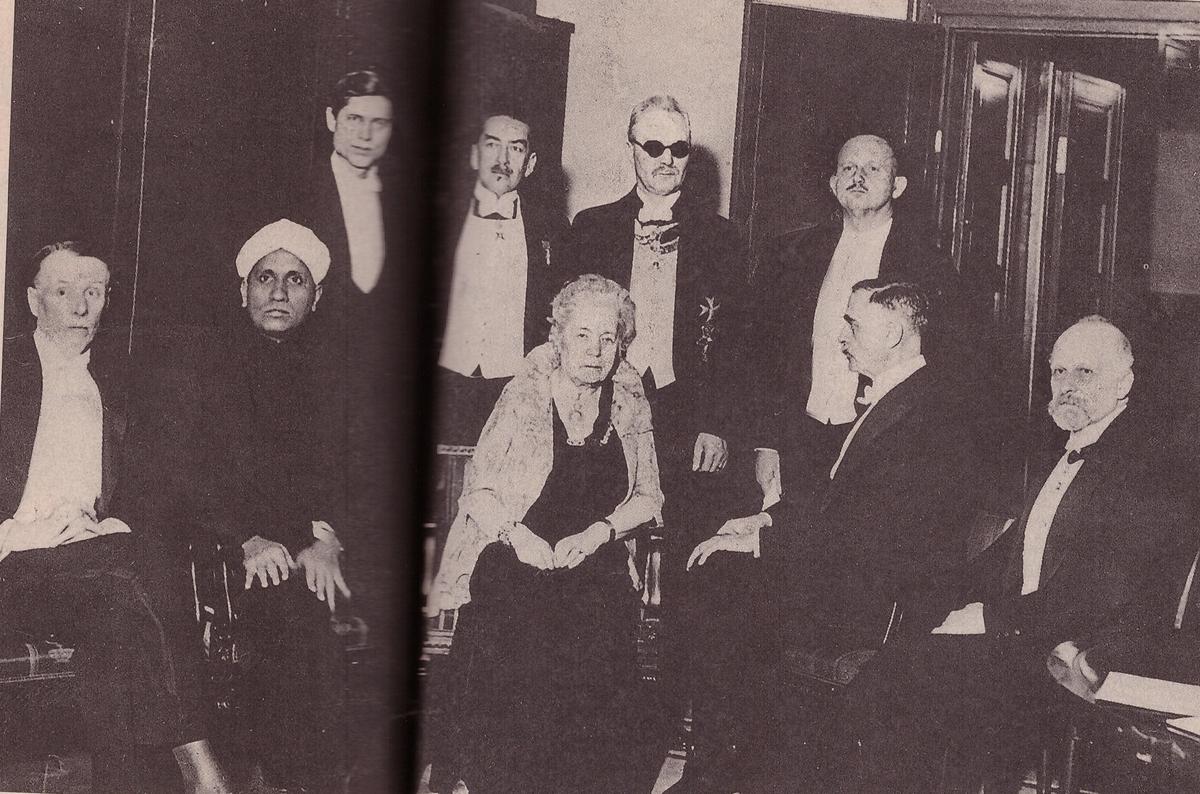

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

The picture shown here is from The Hindu’s archives. This image’s caption mention both Svedberg and Indian physicist C. V. Raman. While there’s no doubt that Raman is the one seated second from left, the same cannot be said about Svedberg. Even though he could be the one standing behind Raman, it can’t be proven beyond doubt.

Image searches on the web and AI-based results throw into question the possibility of Raman and Svedberg being in the same frame. Barring the caption in the archives, there’s no known recorded mention online where the two scientists have been in the same gathering. In such a situation, it is impossible to conclude that the two men might have ever met.

What we do know, however, is that Svedberg was a fellow of the Indian Academy of Sciences. He was elected into the honorary fellowship in 1935, a year after the society was founded in 1934. This is an irrefutable fact that finds mention both in Svedberg’s biographical entry on the Nobel Prize website and in the Fellows’ portal of the Indian Academy of Sciences.

This does hint that there might be a working relationship between Svedberg and Raman as the Indian Academy of Sciences was the brainchild of the latter. Raman founded the society in Bengaluru “with the main objective of promoting the progress and upholding the cause of science.” When the Academy began functioning with 65 Founding Fellows in 1934, it elected Raman as its president in its first general meeting. Considering that Svedberg was elected an honorary fellow the very next year, the two men might well have known each other.

Published – June 01, 2025 12:11 am IST