Charon’s discovery

The story of Charon’s discovery takes us back to 1978 – a time when even astronomers were still thinking that Pluto was a planet. Little was known about Pluto and its system, but all that was about to change in the decades that followed.

On the morning of June 22, American astronomer James Christy already had his head whirling around. If you were under the impression that he was zeroing in on the solution for an astronomical problem, you couldn’t be further from the truth. Christy was sharpening his plans to move his house, getting ready for a week’s leave from the U.S. Naval Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona – his workplace.

It was under these circumstances that Robert Harrington, his boss, handed him a set of six photographs of Pluto. Christy and Harrington were looking to refine Pluto’s orbit around the sun – a journey that takes Pluto 248 Earth years.

Pluto’s average distance from the sun is 5.9 billion km. The technology available at that time meant that even the best photographs of it hardly revealed anything. What’s more, these six images – acquired in pairs over three nights in the month between April 13 and May 12 – were labelled as “defective.”

Odd blobs

The reason why these pictures were labelled thus owed to the fact that they revealed Pluto to be oddly elongated. Viewing them under a microscope, Christy noticed that the fuzzy blob that was to be Pluto stretched in a northern direction in two of those pairs, while the final pair showed a southward direction. The defects were attributed either to atmospheric distortion or improper optical alignment in the telescope used for observations.

After ruling out an explosion on Pluto as an unlikely explanation – especially as it lasted a month – Christy searched for other plausible reasons. There was a chance that Pluto itself was irregular in shape. Or could there be an unseen moon, even though one of his former professors, celebrated Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper, had searched for exactly the same decades earlier without any success?

When Christy went over to the archives to check through older plates from 1965 onwards, there it was… the same elongation. What’s more, all these images had also been dismissed as defective on every occasion.

A handout combination image released by NASA and sent to Earth on July 13, 2015, shows Pluto (left) and its moon Charon, presented in false colours to make differences in surface material and features easy to see.

| Photo Credit:

NASA/John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute via The New York Times

Correct conclusions

Christy and Harrington, however, realised that they were onto something. By reviewing all the images with the elongations, they were able to state that the bulge occurred with a predictable frequency. This frequency of the unseen moon’s orbital period – 6.4 Earth days – matched with what astronomers believed to be Pluto’s rotational period, suggesting a synchronously locked binary system.

The duo ruled out other possible reasons for the bulge and concluded correctly that Pluto had another companion at a distance of 19,640 km. The discovery of ‘S/1978 P1’ was announced by them through the International Astronomical Union (IAU) on July 7 and their findings were published in the Astronomical Journal.

What started out as reviewing six defective images, served as the seeds for a whole new discovery. As Christy himself once pointed out, “Discovery is where the scientist touches nature in its least predictable aspect.”

What’s in a name?

As the discoverer, Christy wanted to exercise his rights for naming Pluto’s companion. And he had his mind set on naming it after his wife.

The Naval Observatory he worked for had suggested the name Persephone, the wife of Hades. Hades, the god of the underworld in Greek mythology, was the equivalent of the Roman god Pluto after which it is named.

As luck would have it, Christy came across a reference to Charon, a boatman who ferried the dead across a river in the underworld to Hades. Charon’s close mythical association with Hades, or Pluto, made it a great option for the newly discovered astronomical object.

It was the perfect option for Christy as his wife’s name was Charlene. In addition to sharing the first four letters, “Char” was the nickname that friends and family used to call his wife. Just like how protons and electrons have the “on” suffix, Christy saw Charon as “Char” with the suffix “on” and submitted his name.

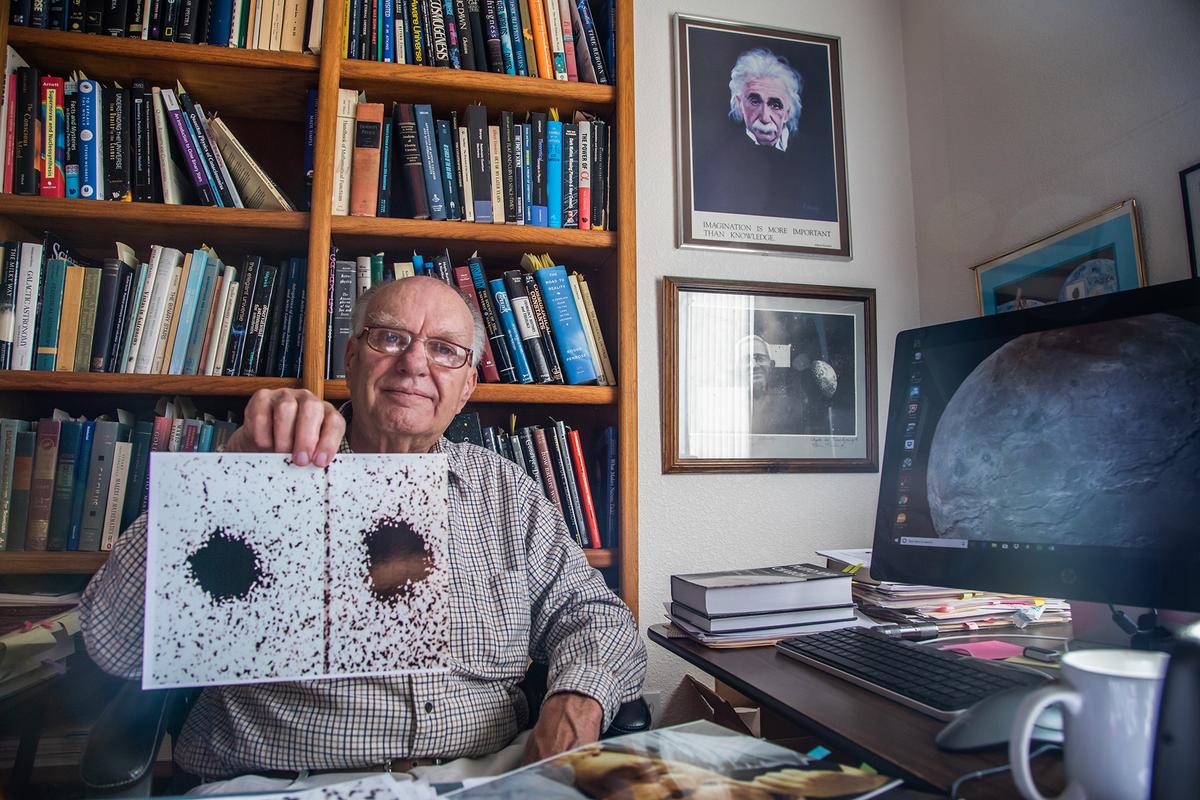

Forty years after his important discovery, Jim Christy holds two of the telescope images he used to spot Pluto’s large moon Charon in June 1978. A close-up photo of Charon, taken by the New Horizons spacecraft during its July 2015 flyby, is displayed on his computer screen.

| Photo Credit:

NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Art Howard/GHSPi

Eclipses and occultations

By the time this name was accepted by IAU in January 1986, Pluto and Charon had a series of mutual eclipses and occultations. Studying them enabled astronomers in general, and Harrington in particular, to confirm the existence of Charon as he observed the eclipses and occultations to occur as predicted.

Observing Pluto and Charon in this manner also enabled astronomers to arrive at Charon’s diameter to be about 1,200 km, while also arriving at better estimates of the size and mass of Pluto.

From a small dot in a photograph, Charon had become much much more – almost a world in its own right. It definitely meant the world to Christy in more ways than one, as he was also able to gift his wife the moon! Charlene Christy probably summed it the best when she said “A lot of husbands promise their wives the moon, but Jim actually delivered.”

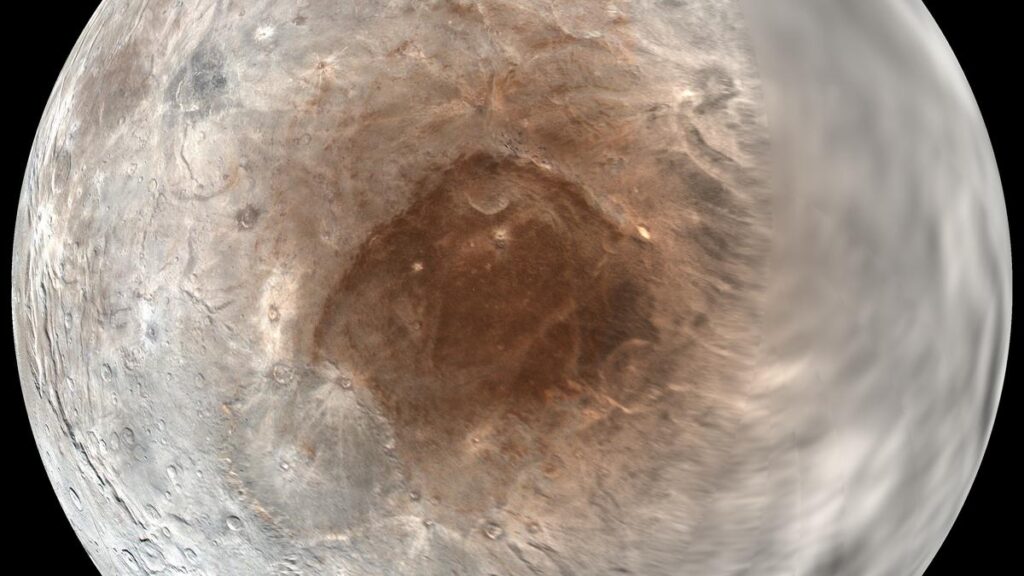

This NASA image released October 1, 2015 shows Pluto’s moon Charon in enhanced colour.

| Photo Credit:

NASA Handout/ AFP

Charon fact sheet

Most of what we know about Charon, or even Pluto for that matter, is thanks to NASA’s New Horizons mission. Approved in 2001 as the first flyby of Pluto and its largest moon Charon, it was launched in January 2006. This was months before IAU’s decision in August the same year to demote Pluto’s designation from a planet to a dwarf planet. Despite the fact that Pluto was plutoed, the mission went on, providing us invaluable information.

Before New Horizons’ closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, the spacecraft captured plenty of images of Charon. While the images revealed a striking reddish north (top) polar region, Charon’s colour palette wasn’t as diverse as Pluto’s. The origins of this red colouration is a mystery for now and no other icy object in the solar system sports a similar feature.

Charon is 1,214 km across and is at a distance of 19,640 km from Pluto. As Pluto’s equatorial diameter is about 2,377 km, Charon is nearly half the size of Pluto. This makes it the largest known satellite relative to its parent body for most astronomers. It is this same size, however, that forces other astronomers to consider Pluto and Charon as a double dwarf planet system.

Charon’s orbit takes 6.4 Earth days to go around Pluto. Charon neither rises or sets, however, but instead hovers near the same region on Pluto’s surface. The same surfaces of Charon and Pluto always face each other due to a phenomenon called mutual tidal locking.

Published – June 22, 2025 12:52 am IST