Once upon a time in the scorching expanse of the Sahara, a young Tuareg boy named Iyad ag Ghali watched his father die in a doomed rebellion. The year was 1963, and that trauma would leave a permanent imprint. Like many “sons of ’63,” Ghali grew up distrustful of Bamako and hungry for something more. By the 1980s, amid drought and disillusionment, he joined thousands of exiled Tuaregs drifting into Algeria and Libya, where a different kind of revolution was brewing under Muammar Gaddafi’s ever-expanding tent.

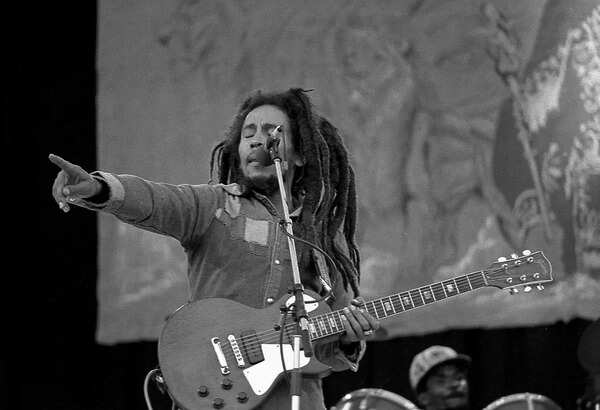

As a profile in WSJ notes, Ghali received military training and soon emerged not just as a fighter, but as a charismatic leader in the Tuareg cause. But this rebel had rhythm. In the refugee camps, he gravitated toward a ragtag group of musicians who called themselves Taghreft Tinariwen — the “Radio of the Desert.” Armed with electric guitars and the poetry of rebellion, Tinariwen gave the Tuaregs a new language: music.

Ghali saw their potential and backed them, supplying gear and rehearsal spaces. He even contributed lyrics and percussion — not with drums, but with metal jerrycans. This was rebellion with a soundtrack. The group would go on to win a Grammy and play with the likes of Bono and Robert Plant. Their benefactor, meanwhile, had other plans.

In 1990, Ghali led a new Tuareg uprising, signing a ceasefire in 1991 after initial gains. He emerged as the face of the rebellion, even representing the Tuaregs at peace talks. But after the guns fell silent and his fellow fighters faded into government jobs or civilian life, Ghali stood at a crossroads. The world was applauding Tinariwen. He had helped them rise. But what about his revolution?

From Rebellion to Religion: A Fundamentalist Turn

In northern Mali, in the late 1990s, a group of white-robed Pakistani preachers arrived from the Tablighi Jama’at. They weren’t carrying guns, but their ideology was potent. Their message: abandon the pleasures of this world, submit to faith, and spread Islamic purity. And somehow, their words found a home in the most unlikely of ears.

Ghali, once a nightclub-hopping chain-smoker who cranked Bob Marley in his car, listened. Then he changed.

Out went the whiskey. In came the beard and the Quran. Friends were stunned. The man who once sang alongside Tinariwen now scolded them for debauchery. He grew distant. By the 2000s, he was spending time in mosques in Bamako and Paris, reportedly brushing shoulders with hardliners. Even diplomats started whispering about his radical turn.

When the Tuareg launched a fresh rebellion in 2011, Ghali saw an opening. But this time, he wasn’t talking about Azawad. He was talking about Sharia. Rejected by the secular MNLA for being too Islamist, Ghali formed his own group: Ansar Dine — “Defenders of the Faith.”

The guitar had been replaced by the gun.

The Rise of Ansar Dine and the Islamist Takeover of Mali

In 2012, as Tuareg and Islamist fighters swept across northern Mali, Ghali’s forces seized key cities. Timbuktu, once the heartbeat of Saharan culture, fell under Ansar Dine’s black flag.

Ghali wasted no time. Music was banned. Instruments were torched. Ancient Sufi shrines were smashed with pickaxes. Women were ordered indoors. Adulterers were stoned. The city became a dystopian nightmare wrapped in religious justification.

France intervened in 2013, pushing the jihadists out of the cities. But Ghali didn’t go away. He retreated to the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains, regrouping for the next act.

JNIM: Coalition of Terror in the Sahel

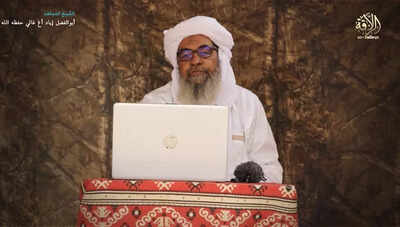

In 2017, Ghali reemerged with a bigger agenda. He merged several al-Qaeda-linked groups into Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and declared himself its emir.

JNIM became a scourge across the Sahel. Its fighters launched deadly raids on soldiers and civilians alike. They ambushed convoys, planted IEDs, and taxed entire villages. In parts of Mali and Burkina Faso, JNIM became the de facto government — settling disputes, collecting grain, and enforcing a warped version of law and order.

Ghali, ever the strategist, tried to brand JNIM as the more “reasonable” jihadist alternative to ISIS. But make no mistake: his fighters still executed villagers, kidnapped women, and massacred those who resisted. In one particularly grim incident, they gunned down 600 people digging trenches for defence.

Regional Fallout and International Response

The chaos sparked by Ghali’s war has toppled governments. Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have all witnessed coups since 2020, with juntas claiming they alone can stop the jihadists. In reality, their policies often play into Ghali’s hands.

The French were kicked out. The UN was sent packing. In their place came Russian mercenaries from Wagner, whose brutality has turned locals further against state forces. Ghali, seeing the backlash, has positioned himself as a protector of the people — all while orchestrating ambushes and extorting communities.

He is now in his seventies, a wanted man with an ICC arrest warrant over his head. Yet he remains free, his fighters entrenched, his reach growing. In the shadows of the Sahel, he continues to orchestrate attacks while preaching piety.

From Beats to Bloodshed

Meanwhile, Tinariwen tours the world, playing to packed audiences in Boston, Berlin and Bamako. Their music speaks of longing and loss — echoes of a dream that once seemed within reach.

But the man who once clapped along beside them is now a ghost in the mountains, a fugitive with blood on his hands. From desert rebel to jihadist warlord, Iyad ag Ghali’s arc is both extraordinary and tragic.

Once, he helped write the songs of freedom. Now, he silences them.